This study originated as the original draft of Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1-1, Strategy (1997). Although it was written under USMC auspices, there is nothing service-specific about it. Rather, it was designed to address the fundamental question, "What is the role of organized violence in the pursuit of political goals?"

While the published version of that manual (right) is essentially a condensation of the original draft, it differs in detail from the full version. In pursuit of the necessary brevity, considerable historical and other explanatory material was removed, much of which we did ourselves in consultation with MCCDC. Later, in the course of staffing the draft through all USMC major subordinate commands, some more traditional geopolitical notions were added. Some of these—"constants and norms" (especially the discussion of climate vs. weather), "national character," and references to some particular US national security policy documents—were in our view irrelevant or contradictory to the manual's overall argument.

While the published version of that manual (right) is essentially a condensation of the original draft, it differs in detail from the full version. In pursuit of the necessary brevity, considerable historical and other explanatory material was removed, much of which we did ourselves in consultation with MCCDC. Later, in the course of staffing the draft through all USMC major subordinate commands, some more traditional geopolitical notions were added. Some of these—"constants and norms" (especially the discussion of climate vs. weather), "national character," and references to some particular US national security policy documents—were in our view irrelevant or contradictory to the manual's overall argument.

This version of the draft is ©Christopher Bassford and has been updated in many places to reflect the continued evolution of a few key ideas and some lessons learned about terminology. [v.4APR2023]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

POLICY, POLITICS, WAR, and MILITARY STRATEGY

by Christopher Bassford

• INTRODUCTION: THE STUDY OF STRATEGY

• CHAPTER 1. THE ENVIRONMENT WITHIN WHICH MILITARY STRATEGY IS MADE

• The Nature of Politics and War

• The Nature of States and Other War-Making Political Entities

• CHAPTER 2. STRATEGY AS A CONCEPT

• CHAPTER 3. WARFIGHTING STRATEGIES

• Sources of Ambiguity in Political Objectives

• Military Strategic Objectives

• The Relationship Between Political and Military Objectives

• Distinguishing Between Erosion and Annihilation Strategies

• Practical Military Objectives, Centers of Gravity, and Critical Vulnerabilities

• CHAPTER 4. SIX MORE SETS OF STRATEGIC OPPOSITES

• Defensive and Offensive Strategies

• Strategy by Intent or by Default

• Iterative or Tailored Strategies

• Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Strategies

• CHAPTER 5. THE MAKING OF STRATEGY

• A SHORT GUIDE TO FURTHER READING ON STRATEGY

• NOTES

INTRODUCTION

The Study of Strategy

"A nation that draws a demarcation between its thinking men and its fighting men will soon have its thinking done by cowards and its fighting done by fools."

—Sir William Francis Butler (1838-1910)

Warfare may appear at first glance to be a simple thing—a cut-and-dried matter of "us against them," a violent clash between two nations or ideologies. Strategy, in turn, may seem a simple matter of deciding how best to use the resources at our disposal to accomplish some clearly defined objective.

This apparent simplicity is a cruel illusion. Warfare is in fact an extraordinarily complex phenomenon. The word "war" itself is nearly impossible to adequately define. States, empires, whole societies and civilizations have gone down in bloody ruin because they failed to master this inherently difficult subject.

Our point here is not that these societies were defeated by outsiders because of military ignorance or incompetence, although that has occasionally happened. Rather, many societies—sometimes embodied in a single political structure, sometimes in a multi-member system—have destroyed themselves through internal warfare. The problem is twofold. Warfare is often used in attempts to resolve problems that simply are not susceptible to a military solution. At the same time, there are always elements in any human society who are willing to use violence to impose their will on others and whose ambitions can be thwarted only via violent means. Accordingly, responsible political leaders must neither overuse nor underuse the military instrument. Either error can cause a society to sink into warlordism or simple anarchy. The fatal step onto the road to self-destruction is as likely to result from an over-reliance on violent solutions as from moderate elements' failure to use force when it is necessary—a classic example of the latter being the Western powers' appeasement of Hitler at Munich in 1938.

Oddly, we sometimes fail to consider the vast social importance of military success, thinking of military victory and defeat as abstractions of importance only to soldiers and politicians. Aside from the obvious dangers faced by a society overrun and conquered by invaders, consider the more subtle social divisions and loss of national self-confidence engendered by the American failure in Vietnam. Those problems were comparatively mild. The French Revolution was preceded by losses in a series of wars—failures that destroyed both the prestige and the finances of the royal government. The Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917 were both the consequences of military defeat, as was the German revolution of 1918. These revolutions eventually brought us Hitler and Stalin. It is clear that defeat in Afghanistan was a catalyst leading to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

We stress these consequences of war in order to remind the reader that war is brutally dangerous. This is true, not merely for the combatants and the innocent bystanders caught in the war zone, but for the larger societies they represent. War means social disruption and the breaking of moral bonds. It breeds hatred, bitterness, and more war. Defeat in war breeds revolution. The path of revolution—however justified the overthrow of the old ruling class, however superior the new society that may eventually emerge—usually passes through a great deal of turmoil, terror, internal strife, and external warfare. It usually leads to dictatorship.

Military events trigger powerful feelings of group identity. They have a disproportionate political impact because of the emotional impact of violence across group boundaries. The political sensitivity of all things military is becoming more obvious, however, because of the high visibility given to such matters by modern news coverage. All personnel must understand that the "distance" between local or tactical actions and the strategic or political level may be very short indeed, and that this distance is highly variable depending on the larger political context. They must adjust their behavior accordingly.

This study is therefore designed to give national security personnel a solid, deep, and common understanding of the fundamental problem of military strategy at the highest level: What is the role of organized violence in the pursuit of our political goals? In other words, how can we most effectively integrate military means—force or the credible threat of force—with the other elements of our power in order to attain our political ends? This study provides conceptual tools that help us to understand both our own and our enemies' political and military objectives, the relationships among them, and thus the unique nature of any particular conflict. Although it gives some consideration to matters of long-term national policy, it focuses primarily on strategies for the fighting of particular wars—that is, on thinking about how to favorably conclude individual episodes of organized political violence. Such episodes are always unique and demand a unique response. A common conceptual understanding helps make possible the flexible, fluid adaptability to such challenges that our strategic concerns demand.

Just as military tacticians need to understand terrain and weather, and pilots need to understand not only the machines they fly but the air currents they move through, military strategists need to understand the fundamental nature of the political and psychological environment in which they operate. Accordingly, this study on strategy reflects war's inherent complexities. It is not designed to provide easy answers. Neither does it seek to provide rigid doctrinal guidelines that offer psychological comfort or legalistic excuses in the event of military failure. Rather, it is aimed at sharpening the judgment of serious national security professionals who understand the heavy burden of strategic responsibility in an uncertain world. National security personnel of every rank should seek to understand its concepts, even though studying war at the political and strategic level may seem irrelevant to their day-to-day duties. There are at least three reasons to make such a study:

• The American national security community is a team. Junior personnel may find themselves working for senior leaders who participate directly in the strategy-making process. Such senior leaders need subordinates who understand their concerns and their intentions.

• It takes time to develop a sophisticated grasp of strategic problems. By the time an individual has assumed strategic responsibilities, it is too late to start studying the basics.

• By the very nature of their profession, all national security personnel are engaged in the execution of strategic policy. Any individual, of any rank, may suddenly find him- or herself in a situation in which his own actions or those of his organization or unit have a direct strategic impact. Therefore, every individual needs to understand how and why this is true.

The strategic environment is overwhelmingly political and psychological in nature, because warfare is nothing but a violent expression of the political process. We are accustomed to thinking of "strategy" as the preserve of the highest levels of political and military leadership, and of the most dangerous levels of warfare. During the Cold War, for example, we used the term "strategic weapon" primarily in relation to nuclear warfare. In fact, however, every military action has strategic—that is, political—implications. This is true in both peacetime and wartime. Sometimes a seemingly unimportant action by an individual actor, perhaps a general, perhaps a platoon leader or even an individual enlisted man, can have a powerful political impact. In 1995, for example, three American servicemen in Okinawa raped a Japanese schoolgirl. In other times, this reprehensible act would have been a matter of interest only to the perpetrators, their victim, and the local authorities. In the political context of U.S.-Japanese relations in the new post-Cold War security environment, however, the crime had strategic ramifications. It threatened U.S. military basing rights in the region and required sustained attention at the highest military and political levels.

Even in traditional, conventional-style combat, commanders at the tactical level may find that political awareness has a strategic payoff. As late as January, 1991, for example, the Saudi Arabian government refused to commit its forces to join in the imminent Desert Storm offensive. The Saudi forces lacked self-confidence and were wary of being seen as junior partners to the Americans. When Iraqi troops seized the Saudi border town of Khafji, the Saudi-American military relationship faced its first serious test. Even though an American reconnaissance team was trapped inside the Iraqi-held town, the U.S. commander on the scene encouraged his Saudi counterpart to take the lead in the town's recapture. By limiting his own unit to supporting actions, the American commander emphasized the role of Saudi forces—and helped them win a dramatic victory over superior numbers of Iraqi troops. This victory boosted Saudi self-confidence and helped inspire the Saudi government to commit its forces to join in the allied offensive.*1

Because of the uniqueness of every strategic problem, it is just as important to understand what this study does not seek to do. It is not concerned with details of current American doctrine or with techniques and procedures for handling military forces in prosecuting a war. That would be a matter of campaign and operational design. It does not prescribe any particular system, intellectual or organizational, for the making of strategy. It does not prescribe any particular strategy or any particular kind of strategy. "Theory," as the great philosopher of war Carl von Clausewitz said of his own work, "is meant to educate the mind of the future commander, or, more accurately, to guide him in his self-education, not to accompany him to the battlefield."*2

Further, despite its general focus on the overall strategy of individual wars, this study is not limited exclusively to any particular "level" of organization or action. Its message is that strategy is fundamentally continuous and indivisible: continuous through peace and war, indivisible from the actions of the squad leader to those of the highest command authority.

This examination of military strategy does not assume that war or military strategy is exclusively a matter of "international" or "interstate" behavior. Therefore, unless referring specifically to states, it uses the more inclusive term "political entity." It does not dwell narrowly on uniquely American strategic issues, but instead emphasizes that strategic thinkers must take into account the strategic concerns and solutions of all the participants in any conflict.

Organizationally, this study proceeds from the general to the specific:

Chapter 1 examines the psychological environment within which strategists operate. It considers the fundamental nature of power, of politics and policy, of human political organization, and of war and its impact on politics and human history.

Chapter 2 offers a broad definition of military strategy. It also examines the relationships among the various "levels" of strategy and considers precisely what it means to discuss the "strategic level of war."

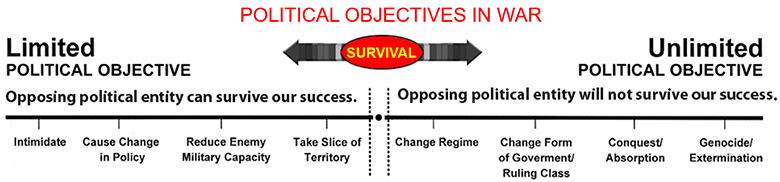

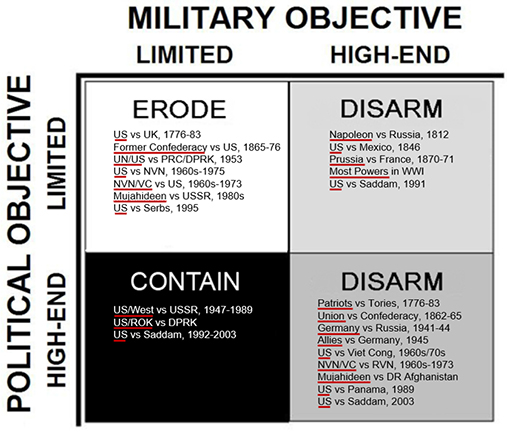

Chapter 3 is, in a sense, the core of the study. It defines the key concepts of limited and high-end political and military objectives and explores two fundamentally different warfighting strategies (traditionally called "strategy of erosion" and "strategy of annihilation"). "Limited political objectives" are those that will permit the political survival of the opposing leadership after we have accomplished our aims; "high-end" political objectives are those that will not. Limited military objectives are those that, if accomplished, will cause the enemy to negotiate a solution satisfactory to us. "High-end" military objectives aim at disarming the enemy, rendering him "militarily impotent."* [Clausewitz, On War, Book One, Chapter Two.] If accomplished, they make the opposing leadership's willingness to negotiate irrelevant: it will be unable to militarily prevent the imposition of our will. The kinds of objective and the fundamentally different methods for achieving them are, in principle, uncoupled. That is, there is no fixed relationship between, for example, a limited political objective and a military strategy of either erosion or annihilation. The way we combine those objectives will depend on the practical situation.

Chapter 4 expands our basis for strategic analysis by examining six pairs of strategic opposites: offensive and defensive strategies; strategies by intent and by default; iterative and tailored strategies; symmetrical and asymmetrical strategies; denial and reprisal in deterrence strategies; and the difficulty of reconciling what is strategically necessary with what is just.

Chapter 5 examines the actual process of making strategy. It considers the various factors that make it difficult to maintain a clear focus on strategic issues and discusses the process of strategic analysis using the concepts in Chapters 3 and 4.

Chapter 1

The Environment Within Which Military Strategy Is Made

[The word] war and the -wurst in liverwurst can be traced back to the same Indo-European root, wers-, `to confuse, mix up.'

—The American Heritage Dictionary

Strategy is essentially a matter of common sense. At its most basic, strategy is simply a matter of figuring out what we need to achieve, determining the best way to use the resources at our disposal to achieve it, then executing the plan.

Unfortunately, in the practical world of politics and war, none of these things are easily done. Our goals are complex, sometimes contradictory, and many-sided. They often change in the middle of a war. The resources at our disposal are not always obvious, can change during the course of a struggle, and usually need to be adapted to suit our needs. And the enemy is often annoyingly uncooperative, refusing to fit our preconceptions of him or to stand still while we erect the apparatus for his destruction.*3

THE NATURE OF POLITICS AND WAR

Before we can usefully discuss the making and carrying out of military strategy, we must understand the fundamental character of politics and the violent expression of politics called war. Let us start by analyzing one of the best known, most insightful, and least understood definitions of war ever written.

"War is an expression of policy with the addition of other means."

"War is an expression of politics with the addition of other means."

—Carl von Clausewitz*4

Note that this definition is presented here in two significantly different forms. Most readers have seen it before, in one form or the other. Most military professionals accept this famous aphorism—albeit sometimes reluctantly—as a given truth. And yet, the words "policy" and "politics," as we use them in the English language, mean very different things. The choice of one of these words over the other in translating Clausewitz's famous definition of war reflects a powerful psychological bias, a crucial difference in our views of the nature of reality. We must understand both relationships—between war and policy, and between war and politics. To focus on the first without an appreciation for the second is to get a distorted notion of the fundamental character of war.

War is a social phenomenon. Its logic is not the logic of art, nor that of science or engineering, but rather the logic of social transactions. Human beings, because they are intelligent, creative, and emotional, interact with each other in ways that are fundamentally different from the ways in which the scientist interacts with chemicals, the architect or engineer with beams and girders, or the artist with paints or musical notes. The interaction we are concerned with when we speak of war is political interaction. The "other means" in Clausewitz's definition of war is organized violence. The addition of violence to political interaction is the only factor that defines war as a distinct form of politics—but that addition has powerful and unique effects.*5

The two different terms we have used, policy and politics, both concern power. While every specific war has its unique causes, which the strategist must strive to understand, war as a whole has no general cause other than mankind's innate desire for power. Thucydides, the ancient Greek historian of the disastrous Peloponnesian War, recounted an Athenian statement to that effect.

Political conflict often turns into war simply because the opponents disagree as to their relative power. The resort to naked force is the only way to determine the truth.*8

Power is sometimes material in nature: the economic power of money or other resources, for example, or possession of the physical means for coercion (weapons and troops or police). Power is just as often psychological in nature: legal, religious, or scientific authority; intellectual or social prestige; a charismatic personality's ability to excite or persuade; a reputation, accurate or illusory, for diplomatic or military strength.

Power provides the means to attack, but it also provides the means to resist attack. Power in itself is therefore neither good nor evil. By its nature, however, power tends to be distributed unevenly, to an extent that varies greatly from one society to another and over time.

Because of its many forms, different kinds of power tend to be found among different groups in most societies. Power manifests itself in different ways and in different places at different times. In Tokugawa Japan, for example, "real" political power was exercised by the Shogun, formally subordinate to the emperor. Later, senior Japanese military leaders were for a time effectively controlled by groups of fanatical junior officers. King Philip II of Spain, whose power was rooted in a hereditary, landed, military aristocracy, launched the famous Spanish Armada against England in 1588. Driven to bankruptcy by his military adventures, he was surprised to discover the power that Europe's urban bankers could exercise over his military strategy. American leaders were similarly surprised by the power of the disparate political coalition that forced an end to the Vietnam War. The resort to violence frequently creates more problems than it resolves: the leaders of the southern Confederacy hardly intended the total destruction of their own way of life when they ordered the shelling of Fort Sumter in April 1861. Two of the major problems of strategy, therefore, are to determine where and in what form "real" power lies at any particular moment and to identify those relatively rare points at which military power can actually be used to good effect.

Power is often a means to an end, perhaps to carry out some ideological program: to create a "workers' paradise," a "place in the sun" for a particular nationality, a "Godly community," a "world safe for democracy." It is also often an end in itself, power for the sake of the prestige, pleasures, or security it brings.

"Politics" is the process by which power is distributed in any society: the family, the office, a religious order, a tribe, the state, a region, the international community. The process of distributing power may be fairly orderly—through consensus, inheritance, election, some time-honored tradition. Or it may be chaotic—through assassination, revolution, and warfare. Whatever process may be in place at any given time, politics is inherently dynamic and the process is under constant pressures for change.

The key characteristic of politics, however, is that it is interactive—a competition or struggle. It cannot be characterized as a rational process, because actual outcomes are seldom (if ever) what was consciously intended by any one of the participants. Political events and their outcomes are the product of conflicting, contradictory, sometimes compromising, but often antagonistic forces. That description clearly applies to war.

"Policy," on the other hand, can be characterized as a rational process. The making of policy is a conscious effort by a distinct political entity to use whatever power it possesses to accomplish some purpose—if only the mere continuation or increase of its own power. Policy is the rational subcomponent of politics, the reasoned purposes and actions of the various individual actors in the political struggle. War can be a practical means, sometimes the only means available, for the achievement of rational policy aims, i.e., the aims of one party in a political dispute. Hence to describe war as an "instrument of policy" is entirely correct. It is an act of force to compel our opponent to do our will.

However, to call war a "mere continuation of policy," the most common translation of Clausewitz's famous sentence, has always provoked objections on two different but equally valid grounds. First, ethical observers object to the amoral implication that violence should be regarded as a routine tool of governments or, even worse, of political factions. Second, experienced practical soldiers and politicians correctly object that any resort to political violence is fraught with difficulty, danger, and uncertainty. It is hardly the convenient, reliable tool that many quoters of this line clearly mean to imply. Both of these objections are aimed at the suggestion that war is a purely "rational" prescription to cure political ills.

Do not, however, confuse "rationality" with either intelligence, reasonableness, or understanding. Policies can be wise or foolish: They can lead towards their creators' goals or unwittingly contradict them. They can be driven by concern for the public good or by the most craven, selfish reasons of interest groups, bureaucrats, ideologues, politicians, or rulers. "Rationality" also implies no particular kind of goal, for goals are a product of emotion and human desire. A political entity's policy goal may be peace and prosperity, national unity, the achievement of theological perfection, or the extermination of some ethnic minority or competitor. No policy-making group enjoys perfect comprehension of the situation, and the best available information (or, at least, the information that policy makers choose to believe) may be completely erroneous.

Remember too that policy, while it is different from politics and is a product of rational thought, is produced via a political process. Even the most rational of policies is often the result of compromises within the policy making group. Such compromises may be intended more to maintain peace or unity within the group than to accomplish any particular purpose. They may, in fact, be irrelevant or contrary to any explicit group goal.

Policy is therefore often ambiguous, unclear, even contradictory. It is subject to change—or to rigidity when change is needed. This lack of clarity may be the result of poor policy making. On the other hand, a vague policy may represent the only way to avoid an awkward or dangerous fracturing of the policy-making group. Ambiguity may be needed to delay some dubious course of action advocated by a powerful sub-group, one that cannot be overtly overruled. Or the lack of clarity may be a way for leaders to keep their subordinates and potential rivals weak and disunited, without siding clearly with any of them.

Such internal political struggles exist within any political entity, even those that outwardly appear to be monolithic. Many brilliant political leaders—queens, popes, dictators, presidents, clan elders, guerilla chiefs—have been masters of ambiguity. This is not a character flaw, although it may appear so to military professionals.*9 Rather, it is a political necessity. It is also, of course, a potential vulnerability.

Clausewitz's reference to war as an expression of politics is therefore not a prescription but a description. War is a part of politics. It does not replace other forms of political intercourse, it merely supplements them. It is a violent expression of the tensions and disagreements among political groups, simply what happens when political conflict reaches an emotional level that sparks organized violence.*10 And violence in turn evokes powerful emotions, perpetuating a vicious circle. Thus war—like every other phase of politics—embodies both rational and irrational elements. Its course, however, is the product not of one will but of the collision of two or more wills.

To say, then, that "war is an expression of both politics and policy with the addition of other means" is to say two very different things to strategy makers. First, it says that strategy, insofar as it is a conscious and rational process, must strive to achieve the policy goals set by the political leadership. Second, it says that such policy goals are called into being, exist, and can be carried out only within the chaotic, emotional, contradictory, and uncertain realm of politics.

Therefore, the soldier who says, "Keep politics out of this: Just give us the policy and we will take care of the strategy," does not understand the fundamental nature of the business.*11 Military strategists must function within the constraints of policy and politics, however awkward this may become. The only alternative is for military strategy to perform the functions of policy and military leaders to usurp political power, for which they are totally unsuited. Soldiers are by nature servants of their societies and make very poor masters. Virtually every attempt by military leaders to subordinate policy and politics to purely military requirements has ended in disaster.

DEFINING WAR

Acknowledging that war is an expression of politics and of policy with the addition of violent means is extremely important. Still, it does not fully define war.

One serious error frequently made in defining war is to describe it as something that takes place exclusively between nations or states. First of all, nations and states are different things. The Kurds are a nation that has no state. The Arabs are a nation with several states. The Soviet Union was a state whose citizens represented many different nationalities. Second, many—possibly most—wars actually take place within a single nation or state, meaning that at least one of the opponents was not previously a state. Civil wars, insurrections, wars of secession, and revolutions all originate within a single political entity, although they also tend to attract external intervention. Wars sometimes spill across state borders without being interstate wars, as in the Turkish conflict with the Kurds.*12

Thus, although we tend to think of war as typically involving one state against another, in fact such wars are unusual. On the one hand, many wars are fought by competing factions within a single state. Most interstate wars, on the other hand, are fought not by individual states but by coalitions. Such coalitions often involve non-state actors. Therefore, any attempt to list different "types" of war or "types" of participants would soon grow too long and complex to be worthwhile. For example, the French state has fought wars against other states, coalitions of states, French Catholic peasants, French Protestant town-dwellers, elements of the French army, and the city of Paris—its own capital.*13

The American military has come to define war as "sustained, large-scale military operations." This approach lumps all other forms of what Clausewitz (and this study) would call war, and some events that are clearly not war, under catch-all headings like "Low Intensity Conflict" and "Military Operations Other Than War." While that approach has its uses, we are concerned with war in all its many guises.

In its broadest sense, war refers to any use of organized force for political purposes, whether that use results in actual violence or not. For a state, the simple act of raising and maintaining military forces has political effects and implications. Increasing the military budget, raising recruitment, signing military alliances, the movement of ground forces or the repositioning of an aircraft carrier, all are implicit threats of military force. The same can be said of non-state political entities. The creation of militias or guerrilla bands is a political use of force whether or not these forces are actually employed in combat. Such non-violent uses of force are as much tools of political and military strategy as any other.

When we speak of actual warfare, however, we almost always mean genuine violence of some considerable scale that is carried out over some considerable period of time. A single assassination, while certainly a violent political act, does not constitute a war.

On the other hand, large-scale, long-term violence alone still does not necessarily mean war. Political violence may be endemic in a society. The point at which people begin to apply the word war to describe it is unpredictable. Mass murder or genocide, for instance, unless they are violently resisted on a large scale and in an organized way, are crimes, not war.

To take a different example, 76 persons were killed in Northern Ireland in 1991, out of a population of 1.5 million. That same year, there were 472 killings in Washington, D.C., out of a population of .6 million. The former situation is widely recognized to be "war," while the latter situation is not. The difference would appear to be a matter of organization. The perpetrators, victims, and targets of the violence in Northern Ireland reflect comprehensible political distinctions between ethnic groups. The violent death rate in Washington, D.C., roughly sixteen times higher, seems to reflect random violence—a sign of social dysfunction rather than of some purposeful movement toward any group's goal.

Because the word war itself has political implications, political leaders are often reluctant to use it. During the Suez crisis in 1956, the British prime minister, Anthony Eden, took refuge in a euphemism and said, "We are not at war with Egypt—We are in a state of armed conflict." Perhaps the decision not to call the Washington, D.C., situation a war is "a continuation of politics by other means": Some would argue that the violence in America's inner cities is a manifestation of class warfare and that "police" SWAT teams are actually specialized military units.

From all this, we can say that war is:

• organized violence

• waged by two or more distinguishable groups against each other

• in pursuit of some political end (i.e., power within some social construct)

• sufficiently large in scale and social impact to attract the attention of political leaders

• over a period long enough for the interplay between the opponents to have some impact on events.

In the final analysis, however, the messy truth is that war is in the eye of the beholder. War defies precise definition and we should not seek one. In practice, political leaders will commit military forces when it appears politically necessary whether or not the situation fits any formal or legal definition of war.

THE NATURE OF STATES AND OTHER WAR-MAKING POLITICAL ENTITIES

Military professionals often seek a "scientific" understanding of war. This approach is appealing because the human mind tends to organize its perceptions according to familiar analogies and metaphors, like the powerful images of traditional Newtonian physics.*14 Such metaphors can be very useful. Our military doctrine abounds with terms like "leverage," "center of gravity," and "mass."

Useful as it is, the attempt to apply this particular kind of "scientific" approach can result in some very unrealistic notions. For example, one widely read military historian recently tried to reduce military power to a simple and, he argued, reliably predictive equation: P=NVQ (where P = combat power, N = numbers of troops, V = "variable factors," and Q = quality of troops).*15 In practice, of course, strategists must seek some understanding of all of these factors. However, even an accurate figure for N is surprisingly difficult to find, while V and Q are impossible to reliably quantify (except through ex post facto number-juggling). This kind of mathematical approach, even though it reflects some important truths, cannot serve as a practical basis for strategic analysis and prediction.

Similarly, many political scientists treat political entities as "unitary rational actors," the social equivalents of Newton's solid bodies hurtling through space. Real political units, however, are not unitary. Rather, they are collections of intertwined but fundamentally distinct actors and systems. Their behavior derives from the internal interplay of both rational and irrational forces, as well as from the peculiarities of their own histories and of sheer chance. Strategists who accept the unitary rational actor model as a description of entities at war will never understand either side's motivations or actual behavior. Such strategists ignore their own side's greatest potential vulnerabilities and deny themselves potential levers and targets—the fault-lines that exist within any human political construct. In fact, treating an enemy entity as a unitary actor tends to be a self-fulfilling and counterproductive prophecy, reinforcing a sense of unity among disparate elements which might otherwise be pried apart.

Fortunately, the physical sciences have begun to embrace the class of problems posed by social interactions like human politics and war. Therefore, "hard-science" metaphors for war and politics can still be useful. The appropriate imagery, however, is not that of Newtonian physics. Rather, we need to think in terms of biology, particularly ecology.*16

To survive over time, the various participants in any ecosystem must adapt—not only to the "external" environment but to each other. These agents compete or cooperate, consuming and being consumed, joining and dividing, and so on. In fact, from the standpoint of any individual agent, the behavior of the other agents is itself a major element of the environment. The collective behavior of the various agents can even change the nature of the "external" environment. For instance, certain species, left unchecked, can turn a well-vegetated area into a desert. Such changes in the environment will, in turn, necessitate and reward adaptive changes elsewhere in the system. And, of course, the environment can also be changed by the intrusion of external factors, setting off yet another round of adaptations.

A system created by such a multiplicity of internal feedback loops is called a complex adaptive system. Such systems nestle one inside the other, constructing, interpenetrating, and disrupting one another across illusory "system boundaries." Any individual member of a plant or animal species, for example, is a complex adaptive system made up of cells. Its protective skin or shell encloses an environment quite different from that outside the system the cells collectively have created. That individual, in turn, is part of larger complex adaptive systems. It is part of a local breeding population that is part of a species, both of which have an existence above and beyond the individual organism. Both the individual and the species it is part of belong to another order of complex adaptive system, the local ecosystem. And so on.

Such systems are inherently dynamic. Although they may sometimes appear stable for lengthy periods, the complex network of interconnected feedback loops demands that its subcomponents constantly adapt or fail. No species evolves alone; rather, each species "co-evolves" with the other species that make up its environment. The mutation or extinction of one species in any ecosystem will have a domino or ripple effect throughout the system, threatening damage to some species and creating opportunities for others. Slight changes are sometimes absorbed unnoticed by the system. Other slight changes—an alteration in the external environment or a local mutation—can send the system into convulsions of growth or collapse. Sometimes both simultaneously.

One of the most interesting things about complex adaptive systems is that they are inherently unpredictable. It is impossible, for example, to know in advance which slight perturbations in an ecological system will settle out unnoticed and which will spark catastrophic change. This is so, not because of any flaw in our understanding of such systems, but because the system's behavior is generated according to rules the system itself develops and is able to alter. In other words, a system's behavior may be constrained by external factors or laws, but is not determined by them. Every system evolves according not only to general laws but to local rules established by evolution, accident, and happenstance—and, if an intelligent agent is involved, through conscious innovation or intervention.

Another characteristic of complex adaptive systems is that the system itself exhibits behaviors and creates structures which are utterly different from those of the individual agents which create it. Extrapolating from the individual properties of gas molecules, for instance, we could not predict the existence or features of a tornado. Similarly, no individual termite intentionally sets out to build a ten-foot-tall structure that functions as an air-conditioner, yet such hives are common in some areas.*17

For all of these reasons, systems starting from a similar base will come to have unique individual characteristics based on their specific histories. Science can describe and often explain the evolution and behavior of a complex adaptive system, but cannot predict it. Oftentimes, however, the chain (or web) of events is so subtle and convoluted, and the evidence so fragmentary, that the sequence of events and the web of causation can never be satisfactorily understood, even in retrospect. Like the tornado's, their behavior cannot be predicted based on an understanding, however detailed, of the individual agents they comprise: We must always consider the system as a whole rather than as a collection of independent parts.

The reason we dwell on the complex adaptive system is that it provides so much insight into human political constructs. Any group of humans who interact will, over time, form a unique system broadly similar to the ones we have described. Humans build all sorts of social structures and engage in complex behavior. Human structures include families, tribes, clans, social classes and castes, secret societies, street gangs, armies, feudal hierarchies, commercial corporations, church congregations, political parties, bureaucracies, criminal mafias, states of various kinds, alliances, confederations, and empires. These structures participate in distinct but thoroughly intertwined networks we call social, economic, and political systems. Those networks produce markets, elections, and wars.

Such networks and structures create their own rules, and are thus fundamentally unpredictable. Economic and political events can be subjected to rigorous analysis before and while they occur, and can be described and often plausibly explained afterwards. Nonetheless, as any regular watcher of the evening news has long since discovered, they cannot reliably be predicted. Indeed, both evolutionary scientists and historians of human events find steady employment in seeking better ways to "postdict" the past, which can be just as puzzling as the present or future. We can certainly see "patterns" in human history, yet history does not repeat itself. "Victory" goes, not only to those participants who learn the existing rules, but also to those who succeed in making new ones.

When we say that politics and war are unpredictable, we do not mean that they are sheer confusion, without any semblance of order. Intelligent, experienced military and political actors are generally able to foresee the probable near-term results, or at least a range of possible results, of any particular action they may take. Broad causes, such as a massive superiority in manpower, technology, economic resources, and military skill will definitely influence the probabilities of certain outcomes. Conscious actions, however, like evolutionary adaptations, seldom have only their intended effects. As many political scientists and historians have wryly observed, there is an unremitting "law of unintended consequences." As the ripples from any one action spread out, their effects unpredictably magnify or nullify the ripples from other actions. Thus actions that seemed at the time to have great importance may prove to lead nowhere, while actions so minor as to escape notice may have tremendous consequences.

Further, human systems are "open" systems, without any clear boundaries. Events wholly outside the range of political and military leaders' vision can have an unforeseen impact on the situation. New economic and social concepts, new religious ideas or the revival of old ones, technological innovations with no obvious military applications, changes in climatic conditions, demographic shifts, all can lead to dramatic political and military changes.

The cumulative effect of all these factors is to make the strategic environment fundamentally uncertain and unpredictable. The onset of war merely intensifies this effect. Enemy actions, friction, imperfect knowledge, low-order probabilities, and sheer random chance introduce new variables into any evolving situation. Events begin to spin out of control. History is too full of examples of great states defeated by seemingly inferior powers, of experienced leaders and armies overthrown by inexperienced newcomers, to believe that politics and war are predictable, controllable phenomena.

Thus it is seldom enough to set a good strategic course and follow it through. As the great German military leader Helmuth von Moltke said, "No plan survives first contact with the enemy." Effective strategists must have a feel for the nature of this environment and be prepared for both the unexpected setbacks and the sudden opportunities it is certain to deliver.*18 Military strategy demands a capacity for both painstaking planning and energetic adaptation to unfolding events.

WAR AND THE STATE SYSTEM

All of the social structures described above—including commercial corporations and church congregations—have engaged in warfare. Nonetheless, we tend to associate war with the state and to blame it on the essentially anarchic nature of the international state system. It is certainly true that the state form of organization has been effective in all forms of politics, including war. It has been so effective, in fact, that virtually all of the world's land surface and its people are now recognized as belonging to some more or less effective territorial state.

As we have already indicated, however, it is wrong to think that war is something that occurs exclusively between states, or that it is a product of the state or of the state system. While it has correctly been said that "War made the state, and the state made war,"*19 even that formula acknowledges that warfare was a pre-existing condition. The anthropological evidence for large-scale human-on-human violence in non-state societies is overwhelming.

The wars waged among primitive peoples tend to look "unmilitary" to modern Western eyes because they seldom involve open battle. They rely on guerrilla techniques, ambush, and frequent but small-scale massacres. However, non-state societies lack the political mechanisms to stop the local feuds, vendettas, and vicious cycles of revenge-killing that plague them. Therefore, such warfare is endemic. It has sometimes proved capable of wiping out whole societies. In a recent survey comparing the rates of warmaking and lethal violence in modern states on the one hand, and historical and still-existing primitive societies on the other, a prominent anthropologist found that:

Historic data on the period from 1800 to 1945 suggest that the average modern nation-state goes to war approximately once in a generation. Taking into account the duration of these wars, the average modern nation-state was at war only about one year in every five during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Even the most bellicose, such as Great Britain, Spain, and Russia, were never at war every year or continuously (although nineteenth-century Britain comes close). Compare these with the figures from the ethnographic samples of nonstate societies discussed earlier: 65 percent at war continuously; 77 percent at war once every five years and 55 percent at war every year; 87 percent fighting more than once a year; 75 percent at war once every two years. The primitive world was certainly not more peaceful than the modern one. The only reasonable conclusion is that wars are actually more frequent in nonstate societies than they are in state societies—especially modern nations.*20

A comparative statistical analysis of annual war death rates showed that, at its worst (Nazi Germany during World War II, for example), the state is occasionally capable of exceeding the highest homicide rates of non-state peoples. On a long-term basis, however, the function of the state, with its determination to keep a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, has been to hold in remarkable check the regrettable but nearly universal human tendency to violence. Averaged over the first 90 years of the 20th century, even Germany's annual rate of war-deaths is lower than that of many typical primitive societies.*21

Therefore, it would be equally accurate to say that "War made the state, and the state made peace."*22 The modern European state system originated in an effort (the Peace of Westphalia) to put an end to one of the bloodiest fratricidal conflicts in Western history, the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). Although warfare between states continued, successful states were able to control the ultimately more costly endemic local warfare typical of non-state societies. To suggest, as one writer hostile to the state recently has, that "the state's most remarkable products to date have been Hiroshima and Auschwitz.... Whatever the future may bring, it cannot be much worse,"*23 is to miss this vital point about the actual role and function of the state.

The state is a stabilizing force in other important respects as well. For example, no territorial state has an interest in seeing nuclear war actually occur. Its own territory and population are hostages. Non-territorial—and thus non-state—political entities, which typically possess no assets targetable by nuclear weapons, are much more likely to actually use any nuclear device that falls into their hands.

The state has not, however, been able invariably to maintain its desired monopoly on the legitimate—that is, the socially sanctioned—use of violence. Entities other than the state make war—most often on each other, but sometimes on the state itself. In either case the state will become involved, either in self-defense or to assert its monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. The monopoly on violence cannot be preserved by an entity unwilling to use violence effectively. Should it fail to involve itself in the struggle, the state will lose a major justification for its existence and will likely find that existence challenged. If the state fails to meet this challenge, it will likely be destroyed, or taken over by some new entity willing and able to take on this fundamental function. This new entity may be another state, or possibly a supranational entity like NATO or the United Nations. Or it may be a new revolutionary government evolving out of what formerly was a non-state entity.

Thus we see that states exist within a rather precarious zone between order and chaos. They are created and maintained by the interaction of various other, hopelessly intertwined but essentially autonomous systems. Leaders and governments have various levers to influence events, but they do not truly "control" their political entities so much as they more or less skillfully "ride the wave." If they impose too much order the system will stagnate and die, like the Soviet Union. If they cease to provide enough coherence, the system will fly apart.

Therefore, we need a mental image of the state more useful than the Newtonian billiard ball model. States (and most other political entities) are tenuous assemblages of disparate, interdependent organisms, conducting an elaborate mating dance along the skeins of an intricate spider web. A tug anywhere on the web affects the whole web, where our patchwork entities occasionally entangle one another, fusing, losing and trading components, and frequently disintegrating.

Perhaps such an image of states and of the international system seems unduly fragile and chaotic. Consider, then, that the United States, which sees itself as a "young" nation, in fact has the oldest constitutional system on Earth. The People's Republic of China is barely 70 years old. Many people alive today were born when most of Europe was actually ruled by kings or emperors. Powerful states and ideologies, commanding formidable and sometimes fanatically loyal military machines, have entered and left the world stage while those people grew up. The Soviet Union [and its empire], one of the most powerful political-military entities in human history, covering [more than] a sixth of the world's surface and encompassing hundreds of millions of human beings, lasted less than a single human lifetime. Responsible strategists therefore sometimes have to think in terms of awkward timespans. These periods may seem beyond the range of practical concerns—that is, beyond the current crisis and even the next election—but strategists and their children will have to live through them.

On the other hand, the sub-components of warmaking entities like states can be remarkably tough and enduring. For example, the British and Japanese monarchies have survived (albeit with radically changing roles) for over a thousand years. The Sicilian Mafia has survived since the 13th century. The origins of the Jews, Germans, Poles, Armenians, and Vietnamese are lost in the mists of antiquity, but they have retained their nationhoods even through periods in which they possessed no states. The state itself can transcend nationality and endure as an idea: The Roman state existed as a distinct entity for nearly 2000 years—but the last government to legitimately call itself Roman existed in another city (Constantinople), worshipped a different religion (Orthodox Christianity), spoke a different language (Medieval Greek), and was based on a political concept altogether different from that of the early Roman Republic which had built the vast Roman Empire in the first place. In yet another guise, Imperial Rome lives on today as the Roman Catholic Church, originally a department of the Roman government created by Constantine and his successors. The Church has in its time maintained armies, secret services, and a powerful bureaucracy. It has fought wars, and in some cases initiated them. This Rome is no longer a state (although it runs a state of its own in the Vatican), but no one would deny that it remains a powerful political entity.

Our point is that, despite the persistence of some political forces and entities, the political movements and individual states and governments that wage wars are remarkably changeable and often fleeting things. In other words, there is nothing permanent about any particular political entity. A state or political movement exists only so long as it serves some powerful set of human needs. Ultimately, its creation, existence, and disappearance depend entirely on its population's willingness to sustain belief. Radical changes in the distribution of power can occur in remarkably short periods.

In 1480, Spain was a collection of little kingdoms, as eager to fight each other as to defend their common interests. Twenty years later Spain held title to half the globe. In 1850, Germany was little more than a geographical expression, a no-man's land between the territories of the great powers. By 1871, Germany was the dominant force in Europe. In 1935, with no armed forces to speak of and an economy in decline, the United States wanted nothing more than for the world to leave it alone. Within ten years, flush with victory, economically prosperous, and in sole possession of the atomic bomb, the United States had become the single most powerful nation on Earth.*24

We stress the fragility of political entities for two reasons. First, it is helpful to remind ourselves of our own vulnerability. Powerful and inspiring as it is, the existence of the grand democratic experiment we call the United States of America is not inevitable. It continues only through the strenuous efforts of its government and of other elements in society which perceive it as a benefit. It can be—and occasionally has been—stressed to the breaking point. Second, it is necessary to remember that every enemy, no matter how seamless and monolithic it may appear, has political fault-lines that may be vulnerable to exploitation.

THE BALANCE OF POWER MECHANISM

One of the most useful approaches to understanding the behavior of political entities is the concept of a balance of power. This concept is a tricky one, however, for the term is used to mean a number of quite different things. In fact, it has no widely agreed-upon meaning. It is nonetheless useful to examine some of the different, often contradictory, ways in which the phrase "balance of power" is used. These contradictions themselves reveal a lot about the nature of politics and the role of war. The balance of power is "at once the dominant myth and the fundamental law of interstate relations."*25

The term balance of power is usually used in reference to states, but it is applicable to any system involving more than one political power center. The phrase can mean any of the following:

1. The actual distribution of power, however unequal that may be.

2. A situation in which two or more entities or groups of entities possess effectively equal power.

3. A system in which entities shift alliances in order to ensure that no one entity or group of entities becomes preponderant.

For our purposes, the most useful meaning of the term is the last given. Balance of power systems have appeared frequently in world history. Normally, such a system is created when several entities vie for supremacy ("hegemony"), yet none individually has the power to achieve it alone. All are suspicious of any potentially hegemonic power, for fear of being swallowed up. Historically, most societies have viewed this as an abnormal situation—the traditional Chinese ideal of uniting "all under heaven" is typical, as was the medieval European ideal of a universal church and empire. After all, there can be only one "best" solution, and that solution logically should apply to all of mankind. Most civilizations have ultimately achieved such unity—and paid for it with stagnation.

Only in the modern European world did the concept of a balance of power gain widespread recognition as a desirable state of affairs. This occurred when it became apparent that no one government or ideology had the power to unite Western civilization by force. Attempts to do so had become so costly and disruptive that they threatened social stability and the dominance of ruling classes everywhere. Gradually, the ideal of a stable system of independent states took hold. After the Peace of Westphalia (1648), most European wars were fought either to maintain the rough equality of the "great powers" or to contain or destroy the occasional "shark" who sought to overthrow the system and impose its hegemony. The object of the system was not peace, but rather the security, freedom, and independence of the participating states.

One of the great debates over the nature of the state system is over whether all states are by nature sharks who would consume their neighbors given the opportunity, or if instead most states are content to coexist peacefully and sharks are the exception to the rule. That debate is essentially unresolvable. It is clear, however, that the periodic arrival of an undeniable shark led to a steady decrease in the number of independent states even in Europe. Even unaggressive states were forced to annex their smaller neighbors as a means of increasing their own powers of self-defense.

Sharks seek to overthrow the balance of power system. Their strategy is to eliminate all competitors (within a state, a region, or world-wide). In the West as a whole, this goal has frequently been attempted but never achieved. Such an effort tends to be disastrous, since it means taking on multiple enemies. Ambitious powers must always be wary of what Clausewitz called the "culminating point of victory."*26 This is the point at which one competitor's success prompts its allies and other potential players to withdraw their support or even throw their weight against it.

Even if successful, the hegemonic solution has its limits. A political entity with no peer competition will most likely stagnate—a case of "nothing fails like success."*27 Because of the internal dynamics of any human system, it is difficult for such a winner to maintain its military edge for long. For example, the reservoir of military experience inevitably ages (with all of the changes in attitude and values that this implies) and eventually dies off. Almost equally inevitably, a new enemy will arise, either from within via civil war or revolution, or from off-stage. World historians have suggested that it was the success of hegemonic states in the Middle East, India, and China that left them so vulnerable to the emerging West, in which there remained the stimulus of furious internal political, economic, and military competition.*28

The conservative strategic solution is to know when and where to stop, i.e., to understand the meaning of the culminating point of victory and to live within the balance of power system. Entities pursuing this strategy are not necessarily altruistic or unambitious. They simply recognize the nature of the system and use it to enhance their own positions.*29 They draw strength from the other members of the system and benefit from the errors committed by sharks. Knowing where to stop, in both their internal and external political struggles, has been a major factor in the consistent strategic success of powers like Great Britain and the United States. The greatest individual practitioner of this strategy was probably the Prussian/German chancellor Otto von Bismarck. In three short wars (1864, 1866, and 1870-71), Bismarck disrupted the European balance of power by unifying most of the small German states into a single, powerful German Empire. Rather than use this power in a dangerous attempt to unify all of Europe, however, he used it to make Germany the new balancing power, working tirelessly to maintain peace among the great powers. His successors, by overplaying their hand, destroyed both Germany and Europe.

Sharks (e.g., Napoleonic France, Imperial and Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union) represent an obvious class of threats to a balance of power system. Less well understood, however, is another kind of threat, the "power vacuum." A power vacuum occurs when there is no authority capable of maintaining order in some geographic area. (We have already discussed this problem in a different context, that of the state unable or unwilling to maintain its monopoly on the use of violence.)

Power vacuums are disruptive to the balance of power in two distinct ways. First, the disorder in the vacuum tends to spread as violent elements launch raids into surrounding areas or as fanatics and criminal organizations commit other provocative acts. The disintegration of Soviet power in the early 1990s has provided many examples of this sort. Another example is the disintegration of Yugoslavia, which drew a reluctant NATO intervention force into Bosnia. Second, the power vacuum may attract annexation by an external power.*30 If this act threatens to add substantially to the annexing entity's power, other states will become concerned and may interfere. Many Russians saw NATO's intervention in Bosnia in this light. NATO's agreement to Russian participation in that mission represented an attempt to mitigate such concerns.

There have been examples of surrounding states peacefully cooperating to ensure that a power vacuum is eliminated in a manner that leaves the balance of power unchanged. For example, Prussia, Austria, and Russia had fought a series of exhausting balance-of-power wars in the 18th century. A new problem arose when Poland, bordered by these three states, became a power vacuum due to its own internal political failures. Eager to evade a new struggle, the three states avoided war by cooperating in three successive partitions of the Polish state. Sometimes, neighboring entities are unwilling to take responsibility for maintaining order in a disrupted area. In that case, they will normally assist some local element to achieve sufficient power to reestablish order.*31

Another example of the problem of power vacuums also helps demonstrate the usefulness of the state form of organization. As a result of the Palestinian Intifada in the Israeli-occupied territories, a de facto power vacuum developed. Israel could prevent the Palestinians from developing their own government, but it could not impose order. Israel had already discovered the difficulties of dealing with a disembodied, non-state terrorist organization, the PLO. Neither problem had proved soluble through military means. Israel has attempted to solve both problems by creating what is, in effect, a Palestinian state. This state can claim legitimacy in the occupied territories and can, in theory at least, be relied upon to put a stop to the turmoil there.

Perhaps more important, a territorial Palestinian state, simply because it is a state and therefore shares certain inevitable characteristics with Israel, is vulnerable to the kinds of pressure Israel can bring to bear. A hit-and-run terrorist organization is responsible only for waging war; the new Palestinian authority is also responsible for picking up the garbage and seeing that the electricity is turned on. In practice, the Palestinian entity is virtually forced to be an Israeli ally against Palestinian elements who want to continue the terrorist campaign.

Thus we have the seemingly paradoxical case of a state helping its enemies to create a state of their own. There is, however, no paradox. Although Israel would no doubt prefer that no Palestinian entity exist at all, in practice that option has proved unattainable. An effective Palestinian state would be easier to deal with than the demonstrated alternative. Resolution of the power vacuum in Palestine would remove a disturbing factor and permit a more stable balance of power system to evolve in the Middle East. Effective strategists must be prepared to acknowledge such realities and to see such possibilities amid the complexities of politics.

However, because the Palestinian proto-state is not a "unitary rational actor," but rather a particularly anarchic example of a complex adaptive system, the greatest threat to both Israel and the new Palestinian authority itself comes from dissident members of the Palestinian nation. Similarly, the greatest threat to the success of this Israeli strategy comes from elements inside Israel.

Strategists must be keenly aware of the dynamics of the various balance of power systems that are involved in any given strategic problem. First, our own strategy will be affected to some significant extent by the internal balancing that takes place between political parties and branches of government, and between various agencies, departments, and services. It takes strong leadership and willpower to prevent the bureaucratic balancing instinct from dominating the strategy-making process.

Second, neutral powers and our allies will be affected by balance of power concerns. The United States is not immune to the culminating point of victory. Many participants in the coalitions we assemble are only temporary comrades in arms, with long-term goals that may diverge widely from ours. Even some of our customary allies have long traditions as great powers and have not necessarily forgotten their own ambitions.*32 Thus our allies' attitudes toward American power are complex. Consequently, a particular victory or setback may either weaken or strengthen our alliances, dependent on the specific circumstances of the conflict.

Third, the balance of power mechanism is operating within the enemy camp as well. During the early stages of World War II, for example, much of Italy's behavior was driven by concerns about her German ally's successes. The resultant Italian actions caused great problems not only for the Western allies but for Germany as well. During the Gulf War, American policy was very concerned about the internal balance of power within a defeated Iraq. The United States desired the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but not if the result was the ascendancy of a radical new Shiite regime.

Like the "invisible hand" of market economics, the balance of power mechanism is always at work, regardless of whether the system's participants actively believe that it is a good thing.*33 It will always influence events, but does not predetermine them. Balancing tendencies can often be overcome by strong leadership, by common interests, by a powerful threat from outside the system. They occasionally break down completely, and a single dominant power emerges. Thus the concept of a balance of power is a useful basis for strategic analysis, and the balancing mechanism is often a useful strategic tool.

Environmental Dynamics

Despite the recurrence of various underlying strategic patterns, the strategic environment can take dramatically different forms depending on what Clausewitz called "the spirit of the age." World War I occurred in a multipolar world dominated by a host of powerful, militarized nation-states vying for national glory. The Cold War, utterly different in character, took place between vast coalitions in a bipolar world riven by the ideological competition between Communism and Liberal Democracy. The two superpowers strove to repress or contain local conflicts everywhere, for fear they might lead to global war.

In the post-Cold War world, we saw a global balance of power that appeared unipolar—dominated by the United States and its Western or Westernized allies—and largely free of fundamental ideological disputes, save in some cases religion. While a unipolar global balance of power seems simple in theory, politics did not stop with America's victory in the Cold War. Regionally, an extremely complex strategic environment emerged. A great many power vacuums were created by the collapse of governments once legitimized by the twisted dream of Communism. Other vacuums were created by the West's abandonment of distasteful, repressive regimes no longer needed as allies against a global enemy. A lucrative worldwide drug trade came to flourish, financing criminal organizations that undermine or even seek to destroy legitimate governments. Burgeoning populations, especially in the littoral regions, threaten to overwhelm the abilities of corrupt or incompetent governments to provide justice and other vital services. Environmental disasters and disputes over resources as basic as water raise regional tensions.

Consequently, the end of the Cold War era saw a host of new conflicts and seemingly new kinds of conflicts—new, that is, to a world grown used to the "long peace" imposed by the extended stalemate of the Cold War. Long-suppressed ethnic, religious, regional, class, and even personal hatreds quickly re-ignited and triggered large-scale violence. The result was often terrorism, civil war, secession, and sometimes the total breakdown of order. In Somalia, for example, the state completely disappeared, swamped by warfare between local clans and gangs.

No longer guided by the Cold War's overarching strategic concept of "containment," American strategists were puzzled by this new strategic pattern. The United States found itself drawn into local, regional, and transnational conflicts by a disparate mixture of internal pressures, economic self-interest, humanitarian impulses, and balance-of-power concerns. Its efforts to adjust to this smaller-scale warfare were not fully tempered by concerns about the possible emergence of a new peer competitor—like, say, Xi Jinping's China—or other strategic surprises, including Russia's atavistic efforts to reassert itself as an imperial power despite its deep inadequacies.

Thus it is vital to understand that history does not actually happen in the neat chronological chunks that characterize many textbooks. No matter how clear the general pattern of conflict may be in any era, there are always exceptions that serve to wrong-foot warfighters too concerned with current fashions or talking-head predictions about "the future of war." It is unwise to over-adapt to temporary trends. The pattern can always change, locally or globally, with little or no warning. As we demonstrated earlier, radical changes in the distribution of power and in the drivers of political conflict can occur on a remarkably short time-scale.

SUMMARY: THE TRINITY

In any particular strategic situation, we can discern certain consistent patterns—like the balance of power mechanism—and use them as a framework to help understand what is occurring now. At the same time, we must realize that each strategic situation is unique. In order to grasp its true nature, we must comprehend how the characters and motivations of the antagonists will interact under specific, often new, circumstances. Summarizing the environment within which war and strategy are made, Clausewitz described it as being dominated by a "fascinating trinity":

War is thus not only a true chameleon, because it changes its nature to some extent in each concrete case, but It is also, when it is regarded as a whole and in relation to the tendencies that dominate within it, a fascinating trinity—composed of:

1) primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which are to be regarded as a blind natural force;

2) the play of chance and probability, within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and

3) its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to mere intellect.

The first of these three aspects concerns more the people; the second, more the commander and his army; the third, more the government. The passions that are to blaze up in war must already be inherent in the people; the scope that the play of courage and talent will enjoy in the realm of probability and chance depends on the particular character of the commander and the army; but the political aims are the business of government alone.

These three tendencies are like three different codes of law, deep-rooted in their subject and yet variable in their relationship to one another. A theory that ignores any one of them or seeks to fix an arbitrary relationship among them would conflict with reality to such an extent that for this reason alone it would be totally useless.

The task, therefore, is to keep our theory [of war] floating among these three tendencies, as among three points of attraction.

What lines might best be followed to achieve this difficult task will be explored in the book on the theory of war [i.e., Book Two]. In any case, the conception of war defined here will be the first ray of light into the fundamental structure of theory, which first sorts out the major components and allows us to distinguish them from one another.*34

In other words, Clausewitz concluded that the strategic environment is shaped by the disparate forces of emotion, chance, and rational thought. At any given moment, one of these forces may dominate, but the other two are always at work. The actual course of events is determined by the dynamic interplay among them.

Note that technology is not a part of Clausewitz's trinity. It is politics, not technology, that determines the character and intensity of war. Modern technology, with its awesome killing power, may be applied with great restraint, depending on policy objectives and political constraints. At the same time, in a conflict propelled by powerful ethnic hatreds and fear, half a million people can be slain in a few days with machetes—as happened in Rwanda in 1995.

Thus the strategic environment is always defined by the character of politics and the interactions among political entities. This environment is complex and subject to the interplay of dynamic and often contradictory factors. Some elements of politics and policy are rational, that is, the product of conscious thought and intent. Other aspects are governed by forces, like emotion and chance, that defy any purely rational explanation. The effective strategist must master the meaning and the peculiarities of this environment.*35

Chapter 2

Strategy as a Concept

You [military professionals] must know something about strategy and tactics and logistics, but also economics and policy and diplomacy and history. You must know everything you can about military power, and you must also understand the limits of military power. You must understand that few of the problems of our time have been solved by military power alone.

—John F. Kennedy

Strategy, broadly defined, is the process of interrelating ends and means (or "intentions and capabilities," or "interests and resources"— different pairs of terms that convey essentially the same meaning). Strategy is thus both a process and a product. When we consciously apply this process to a particular set of ends and means, the product (i.e., "the strategy") is a specific way of using specified means to achieve specified ends. Defined in this broad way, strategy pervades virtually all human endeavors, from finding food, shelter, transportation, and a mate to solving scientific and mathematical problems. It is interesting, therefore, that the word we use to describe this pervasive process has purely military origins: It is derived from strategos, the Greek word for general, and means literally the art of generalship.

In this book, our interest in strategy is of course largely restricted to its applications in war. Even then, however, if we think of strategy in its generic sense of interrelating ends and means, virtually everybody at every military echelon is a "strategy maker." Therefore, to impose some analytical order on our consideration of military strategy, military theorists have developed a set of conceptual "levels" of war: the tactical level, the operational level, and the strategic level. The tactical level is the province of forces conducting actual combat engagements and battles. The operational level encompasses the actions of military forces at a larger scale, coordinating and giving coherence to various subordinate tactical actions. The strategic level of war is the level at which military activities have a direct impact on politics and policy.