|

The Clausewitz Homepage |

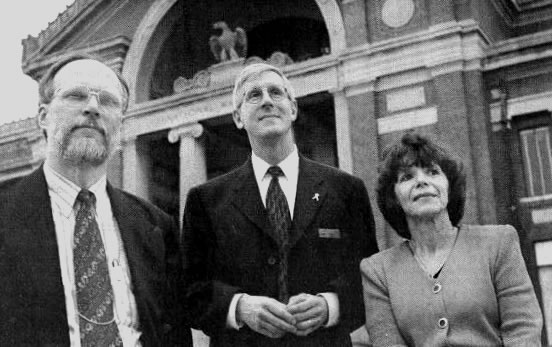

Military Theory and By Joel Achenbach

When people go into that riff about the new, impersonal, remote way of war, about the way laser-guided munitions and satellite-based information networks and all that technological whiz-bang gadgetry has fundamentally altered the very human, raw, gutty tradition of the lone gladiator, Christopher Bassford thinks backs to the moment when one of the kings of Sparta first saw a new contraption for killing people at a distance. It was a catapult. "Woe," he said, "the valor of man is extinguished!" Bassford is professor of Strategy at the , a cathedral of military theory at Fort McNair. The students here are mostly colonels and lieutenant colonels, plus some civilians from intelligence agencies. Even when there's a live war on TV they go to classes to study the textbook version. Here you'll find Lani Kass, a former Israeli air force major who teaches an elective course on "surprise and deception." When asked if war has changed, she gives a slow, solemn answer: "Warfare has changed. War has not." Which means?

"Warfare is how you wage war, the conduct of war. War, the nature of war, is eternal. It has enduring characteristics. Violence. Passion. Enmity. Which transcend time and space." This is one angle on the war we see on TV, that it's really the same old thing, that the more war changes the more it remains the same. But there's another view in play, that war is utterly different now, that there's been a Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA, in keeping with the rule that all military concepts must turn into acronyms). Some thinkers say this notion has been oversold, that every general in every war thought he had reinvented the process of organized violence. But everyone concedes that the new technologies are dramatic. The man commanding the war in Iraq, Gen. Tommy Franks, opened his briefing yesterday by trumpeting the novel elements of his battle plan: "This will be a campaign unlike any other in history," he said, "a campaign characterized by shock, by surprise, by flexibility, by the employment of precise munitions on a scale never before seen, and by the application of overwhelming force." This is one angle on the war we see on TV, that it's really the same old thing, that the more war changes the more it remains the same. But there's another view in play, that war is utterly different now, that there's been a Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA, in keeping with the rule that all military concepts must turn into acronyms). Some thinkers say this notion has been oversold, that every general in every war thought he had reinvented the process of organized violence. But everyone concedes that the new technologies are dramatic. The man commanding the war in Iraq, Gen. Tommy Franks, opened his briefing yesterday by trumpeting the novel elements of his battle plan: "This will be a campaign unlike any other in history," he said, "a campaign characterized by shock, by surprise, by flexibility, by the employment of precise munitions on a scale never before seen, and by the application of overwhelming force." Such comments are not off the cuff, but use words heavily fraught with meaning in the military theory world. Shock, surprise, flexibility, precision -- these are the basic nouns of conversation in the military-theory bunkers of the Washington area. This is what you hear at the think tanks, universities, entrepreneurial theory-marketing defense firms, and the Pentagon itself. But if you go to the old war college, part of the National Defense University, you'll hear buzzwords from a different era: Passion, objective, friction, will. This is the language of Karl von Clausewitz, who, to hear people talk, is easily the most influential person at the college despite having died of cholera 172 years ago. Mark Clodfelter, a genial fellow who calls himself Clod, is one of several self-described Clausewitzians at the college. His hardback copy of On War is jammed with yellow Post-it notes and annotated in ink to within an inch of its life. "I refer to him as the Great Clause," Clodfelter says, stopping by a bust of the Prussian "Philosopher of War" in the central hall. "You'll notice that he's staring down Colin Powell." Indeed, a bust of Powell (National War College Class of 1976) is directly in the old man's line of sight. In real life, Powell returned the gaze, being admittedly Clausewitzian in his strategy during the first Gulf War, keeping a sharp eye on the political objective, building a broad coalition, and avoiding mission creep. As Clodfelter led a visitor into the building, the "Shock and Awe" phase of the bombing in Baghdad had not yet begun. The reporter ventured that perhaps this could be a relatively immaculate war, that maybe hardly anyone would die. Clodfelter smiled at such naivete. "The Great Clause has something to say about that. War is an act of violence to compel our enemy to do our will. There's no such thing as a pristine war. . . . As long as you fight human beings, it's not going to be bloodless. It's going to be violent and people are going to die." A couple of hours later the B-52s arrived over Baghdad. One of the tricks in war, any theorist will say, is to put military tools in service of an obtainable political goal. The famous formulation of Clausewitz is that war is a continuation of politics by other means (the exact translation varies). This is why, contrary to the urges of countless unschooled and inflamed warmongers ("Bomb 'em back to the Stone Age!"), an intelligent military doesn't necessarily unleash all its weapons. The goal is not to kill the enemy, necessarily, but affect the enemy's will. The Shock and Awe concept, for example, doesn't refer specifically to a heavy bombing campaign, even if that's how it's being discussed in the media. Instead it can involve multiple simultaneous operations to bewilder the enemy. But Clodfelter says that war becomes more complicated the further one goes from a goal of total victory. The stated goal of the Bush administration is a regime change in Iraq, and it has hoped that a full-scale clash of armies might be averted. Clodfelter won't discuss the current war, but the topic at hand prompts him to quote something Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman said as Atlanta burned: "War is cruelty and you cannot refine it." Still, here in this lovely space at the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia, combat seems a long way away. On this Friday morning there's a reception in the central hall, with nibblies and refreshments and explosions of laughter. From the front steps of the old building, finished in 1907, you can see the spot where the Lincoln conspirators, including Mary Surratt, were hanged in 1865. There are tennis courts there now. Inevitably any discussion of the theory of war at a time like this can seem esoteric -- remoteness cubed! But it can also help illuminate the mysterious battle plans half a world away, perhaps even clear away a little of that fog of war. "A lot of people don't like theory," says Bassford. "But everyone's got a theory. You can't function without a theory. Our job sometimes is to tell you what your theory is." This line of work, however arcane at times, is passionate, and thus when the military historian John Keegan took a number of shots at Clausewitz in his book A History of Warfare, Bassford fired back in an essay on his Web site. It's at ClausewitzStudies.org, of course. Over in Falls Church, at a private company called Defense Group Inc., James Wade pours himself a cup of coffee in the kitchenette of his office complex, then settles down to discuss, at leisure, the concept of Shock and Awe. He hasn't watched much of the TV coverage from Iraq because he's got a company to run, he says, with 100 employees. One of the products the firm sells is an emergency response tool, called Cobra, for biological and chemical attacks. But he certainly knows all about Shock and Awe, because he's the co-author, with Harlan Ullman, of the influential and controversial 1996 book Shock & Awe: Achieving Rapid Dominance. The war, he says, "is going really well. It really is the 'Rapid Dominance' concept, too." He's not taking credit. He had nothing to do with the battle plan. But he's a former Pentagon official, and a nuclear physicist, who sometimes has the ear of folks like Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Wade is a believer in the concept of the Revolution in Military Affairs, the idea that precision munitions, sensors and information technology have altered the character of war in the same dramatic way as did the atomic bomb. The advocates of Rapid Dominance don't want to see an American division go head to head with an Iraqi division. They want to see overwhelming force on one side -- ours. The military does not seek a level playing field, a "fair fight" as someone nowhere near the combat zone might put it. The battle of Antietam was a fair fight, by and large, and at the end of the day there were thousands of dead Americans littering the cornfields of Maryland. The United States has such vastly superior technology, and such better training in its fighting force, that any "fair fight" would represent a severe tactical blunder, a battle plan gone awry. "Why should the United States, with our technology and people force, ever put ourselves into a situation where we have one soldier against another soldier?" Wade says. The Shock and Awe aerial campaign is only one element of the larger Rapid Dominance concept, Wade says. The goals include befuddling and disheartening the enemy leadership; establishing "dominant battlefield awareness," using information technology, sensors, satellites, night-vision gear, etc.; and quickly defeating and destroying the enemy with minimal casualties. The book drew criticism for stating explicitly that the military should try to create the same kind of Shock and Awe experienced by the Japanese after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Wade says that passage scares many readers, and shouldn't have been written in the first place. Ullman is surprised to hear his co-author offer such criticism so many years after the fact. "He never said anything then," Ullman says. But he admits that the book was never meant for any audience outside the Pentagon. "Shock and Awe is really not a term for prime time. It's not entirely house-trained," Ullman says. Wade and Ullman believe the real revolution will lead to more discriminate warfare, more precision, fewer casualties. And what about valor? What about the individual warrior? Wade sees him or her as more of an entrepreneur. The soldier is wired to the max, mobile, technologically empowered, more of a free agent, not just a blunt instrument. "These kids are brought up being very comfortable with computers. Turn 'em loose! Let 'em go!" Technology, ultimately, is just a trapping of war, an accessory. To pilot an A-10 Warthog or Apache helicopter into the combat zone, or parachute behind the lines in a secret Special Forces operation, or ride in the lead tank at the point of the infantry spear, still requires individuals with great courage. Lani Kass has a formulation that might well apply to what is happening half a world away: "Technology is an enabler. Technology is that aspect of warfare that changes. The human element -- war always being a contest of will -- is an aspect of the eternal nature of war." And thus perhaps the valor of man is not extinguished. |

Return to The Clausewitz Homepage